Advertising in the shade

HAVANA – The folks at La Pachanga got up early on May 1, 2012. “Self-employed workers. We’re here!” said their sign. Below, their motto: “The choice of entertainers.”

“We have always paraded and we don’t look for publicity because we’re also workers,” said Sergio Alba, the cafeteria’s owner. However, their presence at the May Day rally can be seen as a way to expose services that still can’t find institutional channels for promotion in Cuba.

Advertising is not contemplated among the procedures used in the operation of private enterprises. What isn’t advertised doesn’t sell, any vendor will tell you. And in this legal limbo coexist a vigorous sector with a need to communicate and individuals who have learned to take advantage of that need in an ingenious manner.

Advertising is not contemplated among the procedures used in the operation of private enterprises. What isn’t advertised doesn’t sell, any vendor will tell you. And in this legal limbo coexist a vigorous sector with a need to communicate and individuals who have learned to take advantage of that need in an ingenious manner.

Faced with a minimal promotional option conceived by the State for self-employed entrepreneurs, other advertising practices emerge with various degrees of reach and form: fliers, massive SMS, business cards, profiles in Facebook, web pages, stickers, advertisements in foreign publications — a heterogeneous scenario driven by the dialectics of supply and demand.

THE OVEN IS READY FOR PASTRIES

“Seeing how little information was available on businesses that were starting to grow, on the services they were offering, and seeing the increase in mobile telephony, we saw a way to bring together technology and advertising,” says Roberto Carlos Vidal, founder of Isla Adentro, a mobile application that promotes private businesses in Holguín, Sancti Spiritus, Matanzas and Camagüey.

“Seeing how little information was available on businesses that were starting to grow, on the services they were offering, and seeing the increase in mobile telephony, we saw a way to bring together technology and advertising,” says Roberto Carlos Vidal, founder of Isla Adentro, a mobile application that promotes private businesses in Holguín, Sancti Spiritus, Matanzas and Camagüey.

The app can be obtained free in several cellphone repair shops. The advertisers pay a monthly fee for inclusion in the directory.

Other business owners have embarked in advertising campaigns that don’t imply expenditure. Alexander Ramos, one of the owners of El Cocinero restaurant, says that the courtesy of some journalists has worked for them and so has the fact that many of the restaurant’s customers work in the world of art, culture and the media. That generates a traffic of influences, a word-of-mouth that benefits the status of the eatery.

The stage presentation of “Skyscrapers,” directed by Jazz Vilá, at the Llauradó Theater, specifically mentions places like La Catedral and El Cocinero. “We are friends and I help him. It wasn’t something where I had to pay a certain amount,” Alexander says.

But the product placement is evident, from the sandwiches the actors eat onstage to the design of the program handed out to the audience.

This strategy is not new, especially for established brands like Cristal beer, Bucanero beer and Havana Club rum, for example, whose logos are seen everywhere in concerts, TV soap operas, sports programs, etc.

But now, private businesses are also entering this field of indirect advertising that is placed onstage next to the players. That influx could alter the content of a cultural proposal with broad reach and might compromise the pact between artist and audience.

For her part, Elisa Gamboa, owner of the Sancho Panza grill, places advertisements in several foreign publications distributed in Cuba: Cuba Contemporánea, Excelencias, Cubaplus, TTC and OnCuba.

“You have to know how well known your business is,” she says. “I would never do something like handing out leaflets on the street. It has be something that’s better aimed, more organized.” Her team includes a person who handles all the advertising and developed the grill’s website.

Many designers, photographers, and programmers find in private advertising a space for professional accomplishment that’s well paid. However, while people who are involved in public communication for a business are often hired permanently, some say that that kind of initiative is not a stable source of employment.

“Some [business owners] decide to order a video on the spot, and they call up the nearest specialist. But they’re not sure what they want to do. I produce material and I don’t know what they’re going to do with it,” says Alejandro Vallejo,* an audiovisual producer, adding that other business owners do come up with better-conceived ideas.

The professionals have the advantage of experience and the contacts gained in the state-run institutions where many of them have worked. Champola Audiovisual Solutions will soon be a new advertising agency created by four young producers.

“This is our specialty and we’ve decided to hit hard with what we know we can do,” says Juan Caunedo, one of the four. “We’re not the kind who draw up blueprints.”

The concept of filling the blanks is utilized by the team of AlaMesaCuba, who focus on the needs of the users. Ariel Causa, coordinator, stresses the social nature of the project. The value of the advertising is not only in the directory of restaurants but also in the reviews, commentaries and added information that AlaMesaCuba uploads to the web as the proprietors request.

The concept of filling the blanks is utilized by the team of AlaMesaCuba, who focus on the needs of the users. Ariel Causa, coordinator, stresses the social nature of the project. The value of the advertising is not only in the directory of restaurants but also in the reviews, commentaries and added information that AlaMesaCuba uploads to the web as the proprietors request.

Another way that some managers invite potential clients is by promotions in spaces where large crowds gather. La Pachanga did it with the May Day parades, also with the crowds that attended the Latin American Cinema Festival.

“There, we handed out leaflets advertising ‘tacos al pastor’ [tacos shepherd-style], that are very popular in Europe and offered a 10-percent discount to those who brought in the leaflets. It didn’t matter where the customers got them. What I wanted was a full house. And the promotion worked,” the owner says.

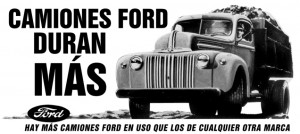

One of the broadest forms of distribution for this type of advertising is the “weekly package,” which works as a powerful offline tool for product placement. There, you find very primitive ads, short on finesse, with a predominance of kitsch.

One of the broadest forms of distribution for this type of advertising is the “weekly package,” which works as a powerful offline tool for product placement. There, you find very primitive ads, short on finesse, with a predominance of kitsch.

“The package” reaches even the Intranet of universities. Its broad reach allows Vistar magazine, which covers the entertainment scene and promotes consumption associated with entertainment, to profit from its advertising, even though it’s only promoted through this outlet.

Most interviewees mention the high cost of advertisements and profiles in aps.

“We have spent a lot. I believe that advertising in Cuba is much too expensive,” opines the manager of Sancho Panza. “It’s as expensive as the raw ingredients, which we buy in retail stores at retail prices, and then we have to do contortions to make a profit,” says one of the owners of El Cocinero.

So far, the only state-owned outlet for self-employed entrepreneurs to advertise consists of ETECSA’s Yellow Pages.

“It has about 4,000 pages and nobody reads them, except perhaps a little old man sitting at home — and he’s not going to come here. They [the phone company] approached us, quoting a very high price, but we’re not interested,” says Sergio.

Elsewhere, the National Information Agency (AIN) publishes the journal Ofertas, aimed at the private sector. However, neither space covers the imperative demand of this market niche.

BUT FIRST, A COMMERCIAL BREAK

Havana was a tropical Manhattan, judging from the advertising signs for Coca-Cola, Buick, Esso, etc. In the 1950s, Cuba was seen as an advertising power in the continent surpassed only by the United States. So much so, that the big U.S. brands designed and tested here the campaigns that they would later launch throughout Latin America.

Havana was a tropical Manhattan, judging from the advertising signs for Coca-Cola, Buick, Esso, etc. In the 1950s, Cuba was seen as an advertising power in the continent surpassed only by the United States. So much so, that the big U.S. brands designed and tested here the campaigns that they would later launch throughout Latin America.

After the triumph of the Revolution, the very dynamics of the process caused this practice to disappear. The communications media were nationalized, the advertisers moved out, agencies shut down one by one.

As the goods being offered dwindled, demand fell captive and consumption became homogenized.

Advertising turned into an aberration, it was not required, all the more when it was seen as an expression of a market-driven society contrary to the society that was being constructed.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that commercial messages flourished again, hand in hand with the expansion of tourism, foreign investment and the legalization of dollar holdings.

At the time, various advertising formats were used: movie shows, radio jingles, sports broadcasts and highway billboards. But that experience was short-lived.

Some agencies remain from those years, functioning as appendages for the promotion of state entities. Two examples are Publicitur, which belongs to the Ministry of Tourism, and Publisime, operated by the former Ministry of Steel Industry.

The “Indications on the Production of Commercial Advertising and Publications Circulating in the Country,” issued by the Ideological Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) in 1998, is the only document that regulates this activity.

The text sets several rules, among them: do not appeal directly to consumption, respect the sensitivity of women and children, do not use patriotic symbols or allude to national heroes, and use no more than 30 percent of the printed page for advertising.

However, this document is directed at the ministers and secretaries of the provincial committees of the PCC, so its internal nature excludes it from public distribution.

At this moment, the country’s leadership is working on a Law on Communications, or Law on the Press. Nothing is known about the process or what treatment will be given under it to advertising. At the same time, the Party has urged the media to find ways to finance itself, suggesting that advertising might make a comeback.

To Sergio Alba, an important contradiction lies here.

“They open the door, but the basis of a business is promotion, and if they don’t let you do it they’re not supporting you.” That legal vacuum is causing groups like Champola Advertising Solutions to seek “the best way to offer our services, no matter what we’re called and no matter where we do it,” alluding to the possibility of operating as an advertising agency under a license for a photo studio. Or maybe as a cooperative “until they open up the game.”

Certainly, most actors in the advertising game do not consider an impediment the “non-legal” status of the promotional exercise. All of them have found ways to “sneak in.”

On the other hand, down the line, an increase in foreign investment could allow advertising to take off, even if there is no legal structure to protect it.

Carlos Masvidal, a designer for Habaguanex, believes that the market laws will accommodate, in a “natural” manner, the future of advertising for private businesses.

Meanwhile, it’s worth asking if these forms of publicity, so far cautiously allowed and unregulated, contribute to demonize a practice that’s already stigmatized by ideological criteria.

So long as the State does not take a position, a question mark hovers over the immediate future of advertising in Cuba.

___________

*Not his real name.

CAPTIONS:

PICTURE OF ISLA ADENTRO: “In the computers and telephones with IOS or Android system, there is a huge data base about the businesses operating in the country,” says Roberto Carlos Vidal.

PICTURE OF EL COCINERO: “If there were government advertising — and that would mean serious advertising — of course we’d be interested,” says Alexander Ramos, one of the owners of El Cocinero.

PICTURE OF THE YELLOW PAGES: Classified ads cost at least 10 CUC (US$10)