Women of childbearing age: Are they responsible for the problem?

HAVANA – She is almost 30 years old and has not had children yet. She already feels the social pressure on herself: What are you waiting for? In our society, where there are still deeply rooted gender stereotypes, being a woman, by default, seems synonymous with being a mother. She, however, feels that it is her right to decide when she will have children, and she even wonders if having them is part of her life project. But such an idea she does not express out loud, many would demonize her for it…

During the past number of years there has been a notable decrease in Cuba’s birth rate, a fact that, together with other factors, such as the decrease in the mortality rate — associated with a longer life expectancy — and the negative migratory balance, make the island’s demographic panorama complex, according to specialists in the field. In perspective, this behavior has considerable repercussions on the health and the economy of the country, since it imposes numerous challenges on society.

Cuba has not reached the necessary population replacement rate since 1978. Since then its global fertility rate is less than the 2.1 children per woman needed to achieve this succession.

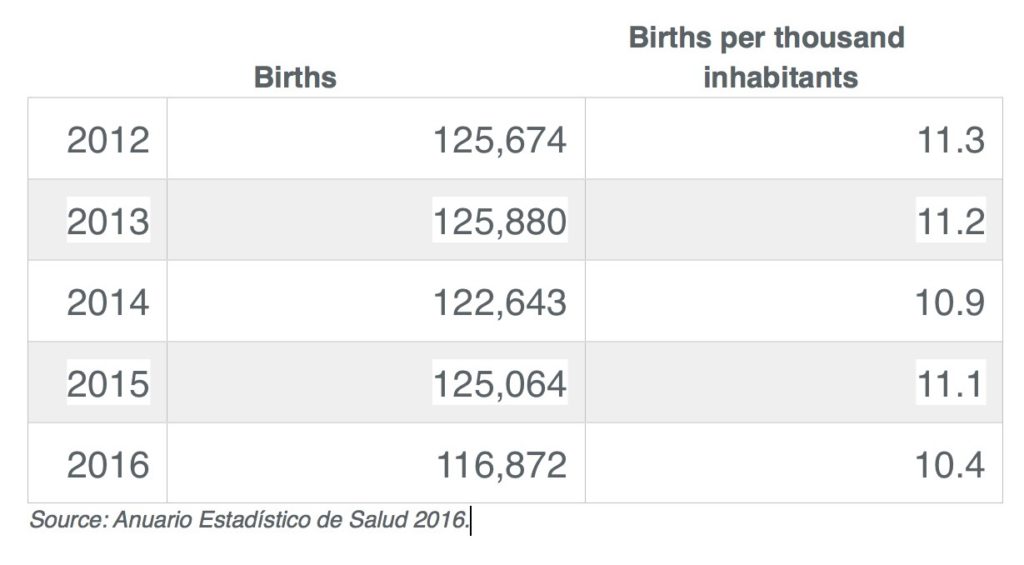

The birth rate in Cuba (number of births per thousand inhabitants in a year) was 11.1 percent in 2015, a slight increase in relation to the previous year. However, in 2016, it suffered a steeper fall than its previous variations: decreasing to 10.4 percent; together with a fertility index (average number of children per woman) of 1.63.

Although generational replacement is a historical problem (an essential aspect when analyzing its causes), the decline in the fertility rate has become much more marked.

Who is to blame for the “problem”? What factors determine it? When and how many children must women bear? Do these figures correspond with their ideal?

In reviewing comments made in articles on the subject, we find diverse and conflicting opinions: from those men who blame women for the “problem” and label them as selfish, to those who recognize and respect the right of each person to decide on their life and what she considers best for herself.

“Simple, women do not have children because there is not enough food, there are not enough houses, there is not enough money, there are not enough resources, there is not enough transportation, there is not enough will in the family,” opined a person in one of the many forums on the subject.

Issues such as the overcrowding of families in a single dwelling, the growing economic difficulties of daily life, and the increased access to education and employment of women in Cuba were reiterated in the exchanges on the web.

The economic impediments to face the astronomical expenses involved in starting or expanding a family has undoubtedly been the most often cited, even by women who confessed having wanted to have three or more children.

Without questioning the existence of each and every one of these reasons for couples to decide to have fewer children and/or postpone motherhood, generalizing these criteria would be wrong without conducting a rigorous investigation that documents and endorses these causes, and all its hierarchy.

Nearly 10 years after the last fertility survey was conducted (2009), a current study of this situation could help us clarify the weight of each of these cited examples as determinants, or not, of the matter.

In this sense, demographer Grisell Rodríguez found that Cuban women put more weight on the economic situation and the housing conditions at their disposal, and added that to their success as professionals — both in the labor market and their personal self-improvement interests.

Thus, while an article published in the Cuban magazine of Public Health recognizes as a limiting element the still present difficulty of housing for couples, another study referred to in the magazine Novedades en Población suggests that many Cubans postpone their maternity as a result of an emigration project.

Another element analyzed by experts is the issue of access to methods of contraception. Cubans have the right to abortion, they have affordable and subsidized contraceptives: all achievements of a health system that is in favor of the ability of each person to decide her sexual and reproductive health, which translates to no unwanted births or “accidents”. Although, this approach may be deemed dangerous today in the face of global and radical religious positions on contraception, qualifying a human right as sin or immoral.

Meanwhile well known sociologist Reina Fleitas, a University of Havana professor in the history and philosophy faculty, is of the opinion that low fertility is also the result of a culture of consumption influenced by “the concepts of well-being that we have created for the care of children and the enormous difficulties that exist to make it viable.”

Certainly consumption sets the trend. In my generation we grew up with cotton diapers that you had to boil after use and then iron one by one. But no one disputes the relief that comes from disposables.

On the other hand, the gender perspective provides critical views on the matter. In private discussions stereotypes continue to predominate placing a major responsibility on women for domestic tasks and care. Women — professionals, technicians, and others who are more involved in positions with high levels of demand, and with professional goals that demand time and dedication to studies — have a great deal of responsibility reconciling work and family life. Therefore the idea of having more than one child considerably increases the workload of which they are already burdened with.

Women do not deny the fact that in recent years some Cuban men are becoming more conscientious that they too must become involved in domestic tasks and assume a responsible fatherhood. But it is about guaranteeing that co-responsibility.

Another matter is the high rates of divorce, which includes the separations of consensual unions. It is a fact that when this occurs, the children most of the time remain under the mothers’ care. Then imagine that if women without children are already demonized what happens to one who, after the divorce, requires the father to take charge of the child full time.

I know that none of these situations can be generalized. In fact, I try not to be an absolutist: I know exceptional parents. Updating laws that guarantee male co-responsibility in the care and maintenance of children is a pending issue. We must also continue promoting a fatherhood involved in raising the child beyond economic sustenance.

The many sides to this matter are all complex. Data suggest that reaching replacement levels will not be viable. Although specialists state that the Cuban socio-demographic situation is essentially irreversible and the result of a positive transitional process, the country must promote laws that guarantee the well-being of couples who decide to procreate.

Cover photo by Roberto Suárez (taken from Moncada).