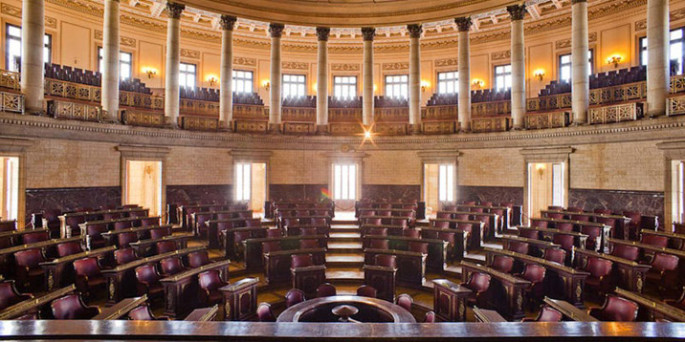

Two hundred seats for Cuba’s legislators

HAVANA — The National Capitol, seat of the republic’s legislative power until 1959, has been home in the past 50 years to various institutions and ministries, such as Science, Technology and the Environment. No longer.

For some time now, its has undergone major repairs to become once again the legislative chamber, that is, the National Assembly of the People’s Power, the institution that constitutionally is Cuba’s highest power.

Recently, Progreso Semanal published a report on the progress of the task, on the delicate condition of some sections of the building and about the sections that have been completed. Among the latter is the Capitol’s North Wing, historical site of the Chamber of Representatives, which has 200 seats.

Will the number of parliamentarians be reduced?

The National Assembly of the People’s Power has 612 deputies for a population of 11.1 million. Proportionally, the relationship is much greater than that of the Chinese legislature, which has 2,985 Assembly members for a population of 1 billion 367 million 820 thousand.

A brief digression. In 1958, Cuba’s legislative power was composed of two houses: the Chamber of Representatives and the Senate. The latter had 54 senators, 9 for each of the then-6 provinces. The lower chamber had 1 representative for each 35,000 inhabitants or fraction above 17,500 inhabitants. Both chambers together numbered 225 members.

The obvious and necessary reduction in parliamentarians forces us to speculate about something the President Raúl Castro Ruz has already announced: the existing Constitution will be reformed and the amendments are being discussed.

But we know very little about that reform, other than apparently it will focus on two important changes: one, in the political-administrative division, a measure that could affect the organization of the election processes. Two, in the likely greater autonomy for the municipalities (very desirable, of course), such as the separation of the municipal and provincial legislatures from the administrative tasks, for which several levels of Committees for the Administration of the People’s Powers (POP) have already been created.

As to the changes in the political-administrative map, there appears to be a tendency to reduce the number of municipalities (168), integrating the eliminated ones into a larger body. If true, will this reduction affect the number of chairs in the Capitol? And what will be the repercussions at the provincial level? Will the current 15 provinces be reduced?

The balcony

I return to the now-concluded North Hall. The balcony, just over the legislators’ chamber, is reserved for the public. Both the 1940 and the 1976 Constitution say that the citizens have the right to observe the sessions. But this constitutional right has not been exercised. Will it be changed? Will it be included in the reform and fully guaranteed?

At present, Cubans follow the Assembly sessions through video excerpts that are edited and shown on television. Often, important statements by parliamentarians and high-ranking officials undergo a peculiar use of “close-captioned reporting,” where an announcer, reading from a script, describes the words of the speakers, whom we see moving their lips. Does the announcer capture the essence of the words spoken by the deputy or leader?

The view that a considerable portion of the population has of the Assembly sessions is that the Assembly is generally reduced to approve the law-decrees issued by the Council of State. And that sector of the population often wonders how often has a minister ever been questioned, or how often the Assembly itself has effectively introduced a law.

Is that a real perception? False? I don’t know. My lack of definition, as well as the doubt in the minds and voices of many other citizens, is a result of the absence of clarity. The solution lies in opening the sessions to the public, both the general sessions and those of the working committees, where, according to some sources, interesting debates occur.

Private sessions should be reserved for debate on issues of national security, something that occurs in practically all the world’s parliaments.

If, as the physical repairs of the Capitol are done, the internal mechanics of the National Assembly are redesigned, rationalizing its composition; and if the Assembly carries out its functions fully, such as questioning and challenging the executive power under the eyes of the population, we Cubans will see more clearly whether we’re well represented in the topmost institution of power.

Progreso Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists so long as source and author are identified.