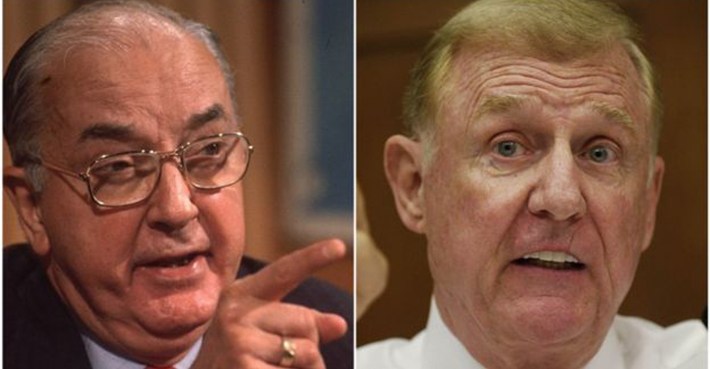

Republicans Jesse Helms and Dan Burton.

Republicans Jesse Helms and Dan Burton.

The true origin of the Helms-Burton Act

HAVANA – In 1998, just two years after the Helms-Burton Act was passed, the Center for Public Integrity (CPI), a well-known nonprofit organization dedicated to journalistic research with the stated purpose of “revealing abuses of power, and corruption of public and private institutions” of the United States, published an extensive report on the origin of this law, which until today has not been refuted (*).

According to the CPI report, it all started when Republican Jesse Helms assumed the presidency of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and proposed a ten-point agenda aimed at changing the direction of the foreign policy of then-President Bill Clinton.

Perhaps because Cuba seemed like one of the few remnants of socialism in the world, the island appeared at the top of this agenda. Nothing else could be expected from a fanatic anti-communist who had voted against the end of racial segregation, the right of homosexuals, the investigations on AIDS, and all the proposals of social benefits that he had before him during his 30 years in Congress.

To carry out this task, Helms appointed his assistant, Dan Fisk, who put together a team that included Cuban-American Republican members of congress Lincoln Díaz Balart and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, as well as senators Bob Menéndez and Robert Torricelli, all who had already worked on previous legislation against Cuba.

As a counterpart to Helms, Republican congressman Dan Burton was chosen in the lower chamber. Burton was head of the Western Hemisphere subcommittee of the House of Representatives despite the fact that one of his most famous proposals was to deploy U.S. ships to the Bolivian coasts (Bolivia has no coastline) in order to stop drug trafficking.

Originally from Indiana, Burton was well-known for his golf game, where he spent most of his time, and also his support for the apartheid regime in South Africa. Although he probably did not know where Cuba stood on a map either, he received more contributions from MiamPi than from his home state.

To take charge of the “Cuban mission,” Burton appointed Roger Noriega, then an obscure House of Representatives aide, whose career revolved around promotion of aggressive U.S. policies towards Latin America.

The CPI report tells us that Chapter I of the law was basically a compendium of the proposals against Cuba Díaz Balart had already presented to Congress. Chapter II, it says, was mostly Bob Menéndez’ handiwork. He was interested in establishing the conditions for regime change and the lifting of the embargo. Chapter IV was nothing new; it recommended sanctions to apply against the foreigners that did not comply with the U.S. dispositions, something quite common in U.S. foreign policy.

However, the CPI considered Chapter III very original, since it introduced a budget to equate property, and human and environmental rights, before international law. For Fisk, at the time still a law student at Georgetown University, if a tortured person could take legal action against his torturers, the same logic should apply to the case of a person deprived of his property by any government anywhere.

Contrary to the widespread notion that the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), at the time the most powerful organization of the Cuban-American extreme right, had been a determining factor in the drafting of the law, the CPI study stated that they did not play a role in this process due to the stridency of their positions. In addition, says the CPI study, the FNCA advocated that properties “recovered” in Cuba be put up for auction, which contradicted the interest of the claimants.

The drafters of the law preferred turning to lawyers and lobbyists of large Cuban businesses nationalized in 1960. In particular, the Bacardí company, which played a decisive role in the process of designing and approving the law. Manuel J. Cutillas, the company’s executive director, and Otto Reich, a lobbyist at the time, as well as Ignacio Sanchez, a partner in the law firm, Kelly-Drye and Warren, a New York-based firm that represented Bacardi interests, played a very active role in the writing of the text and the search for consensus for its approval.

Aside from a long tradition of activities against the Cuban government, which included the backing of terrorist groups, the Bacardí company had a special interest in the Helms-Burton Act because, as the CPI report explains, it was not a Cuban or American company, but registered in the Bahamas, so that thanks to Title III, its subsidiary in Miami could appear as a claimant and appeal to U.S. courts.

Initially the Clinton administration firmly opposed this law. According to the CPI report, this position was officially transmitted to Ricardo Alarcón, then president of the National Assembly of Cuba, by Peter Tarnoff, undersecretary of State, in the context of secret talks between the two governments, which took place in Toronto, Canada, and that concluded with the adoption of the 1994 migration agreement between the two countries.

Summoned by Helms himself in June of 1995, Tarnoff testified before the Senate laying out the administration’s reasoning. First, said Tarnoff, the law violated the constitutional right of the executive branch to conduct the foreign policy of the country, as well as several international treaties, the obligations of the United States before the IMF and the World Bank, and its relations with foreign partners. He added that the law could lead to retaliation which could result in similar measures taken against US companies.

Referring to Chapter III, says the CPI report, Tarnoff warned that if the United States arrogated such powers to its courts, nothing prevented other countries from doing the same. According to Tarnoff, this law would affect the fragile international legal system, which had helped resolve tens of thousands of claims in favor of US citizens in different parts of the world.

Regarding the right on non U.S. citizens to sue in U.S. courts at the time of nationalization, Tarnoff said that under international law the United States had no right to intervene in a matter that corresponded to a foreign State within its own borders.

These arguments, expressed by the administration itself that finally approved the law, should have been enough to disqualify it. But the CPI study also recounts the opposition of the Joint Committee of Claims to Cuba, made up of U.S. companies nationalized in 1960, which included companies the size of Chase Manhattan Bank, Coca Cola and ITT.

According to their spokesmen, “the recognition of another group of claimants would delay and complicate the settlement of certified claims in the negotiations with Cuba.” The adoption of the Helms-Burton Act would also abort direct arrangements with the Cuban government that were being explored by companies such as Amstar, the American Sugar heir, which owned more than a thousand square miles of land in Cuba.

There are those who claim that the ominous Brothers to the Rescue episode where two small planes were blown up as they repeatedly violated Cuban airspace in 1996 led to passage of the Helms-Burton Act. The fact is that all appears to indicate that Clinton’s reason dealt more with assuring the support of the Cuban-American extreme right in that election year.

And now that Title III has been implemented by the Trump administration after 23 years of logical suspension, goes to prove that there is real danger for the party in power in the upcoming U.S. elections for president.

(*) Patrick J. Kiger: Squeeze Play: The United States, Cuba and the Helms-Burton Act, Center for Public Integrity, 1998.