Sugar harvest looks for the perfect double play

HAVANA — Producing sugar has a lot in common with executing a good double play in baseball. Just as two players need to coordinate their movements to put out two opponents in the same play, synchronization is needed between agriculture and industry to extract all the sucrose from the cane.

During the 2015-2016 sugar harvest, only two Cuban provinces, Sancti Spíritus and Ciego de Ávila, managed to complete their double play, which, in this case, was to meet their respective production targets.

On July 26, the vice president of the councils of State and Ministers, José Ramón Machado Ventura, stated that successes like those do not abound in the nation. He has toured several provinces, focusing strictly on sugar-production issues.

During his talks with sugar growers, technicians and business leaders, the vice president said that he will continue the modernization of the mills and cultivation and irrigation equipment in the plantations.

“It is necessary to create a commitment that will impact positively upon the production of cane, increasing the areas that are planted and improving the industrial output of the mills,” he said in January 2015 while in the island’s eastern provinces.

Shared responsibilities, shared blame

After the 2015-2016 harvest, Cuba found itself 20 percent below the target output. At first, the leaders of the Entrepreneurial Group AZCUBA blamed the initiators of the double play: the farmers.

The 50 mills that ground the cane did so with 95 percent of the raw material initially expected. The drought at the time of the rainy season, and the rains at the time of the dry and cold winter caused 71 percent of the losses by affecting the sugar content of the cane and therefore the efficiency of the mills, the millers said.

However, the cases in Sancti Spíritus and Ciego de Ávila illustrate the fact that not all analyses should end by blaming the weather because, for the past several years, both provinces have met their production quotas, i.e., more than 100,000 tons each.

Both provinces suffered the same climate adversities as the rest of the country, but — according to the Spirituan press — there was “sufficient raw material to grind without major worries and an infrastructure (admired throughout the island) capable of reducing the lost industrial time to less than 10 percent.”

In Ciego de Ávila, engineer Miguel Lima Villar, a specialist in the local Sugar Enterprise, pointed out that the farmers’ cohesion enabled three of the province’s four mills to lead the nation in terms of factory efficiency.

That wasn’t the case with other power hitters in the sugar team; the provinces of Matanzas, Villa Clara, Camagüey, Las Tunas and Granma, upon whose shoulders lies the responsibility of extracting significant amounts of sugar. All of them have had erratic performances from one season to the next. The 2015-16 season was no exception.

The Villa Clara target was 250,000 tons; the farmers didn’t even exceed the output for 2014-15. In Las Tunas, which had just halted a long series of shortfalls, production didn’t reach the 185,000 tons predicted.

Industry goes from major to minor

The halt in preferential trade relations with Eastern Europe in 1991 left Cuba without its traditional buyers of sugar. At the same time, prices in the open market plunged (5.75 cents per pound in 2002). Sugar ceased to be the leading source of hard currency, replaced by tourism and the services of Cuban professionals abroad.

Faced with that reality, the Cuban State completely restructured the sugar industry, which at the time utilized 2 million hectares of arable land and employed 450,000 workers. A policy set in 2002 gave priority to efficiency, not to the idea of producing at any cost, which had characterized the 1990s.

Annual production was reduced to a maximum potential of 4 million tons, under parameters of inmovable revenues and costs. Seventy-one of the existing 156 mills were totally dismantled, with unprecedented cultural and social repercussions despite the government’s efforts to cushion the impact as much as possible.

Seventy other factories remained as sugar producers, while 14 turned to producing derivatives.

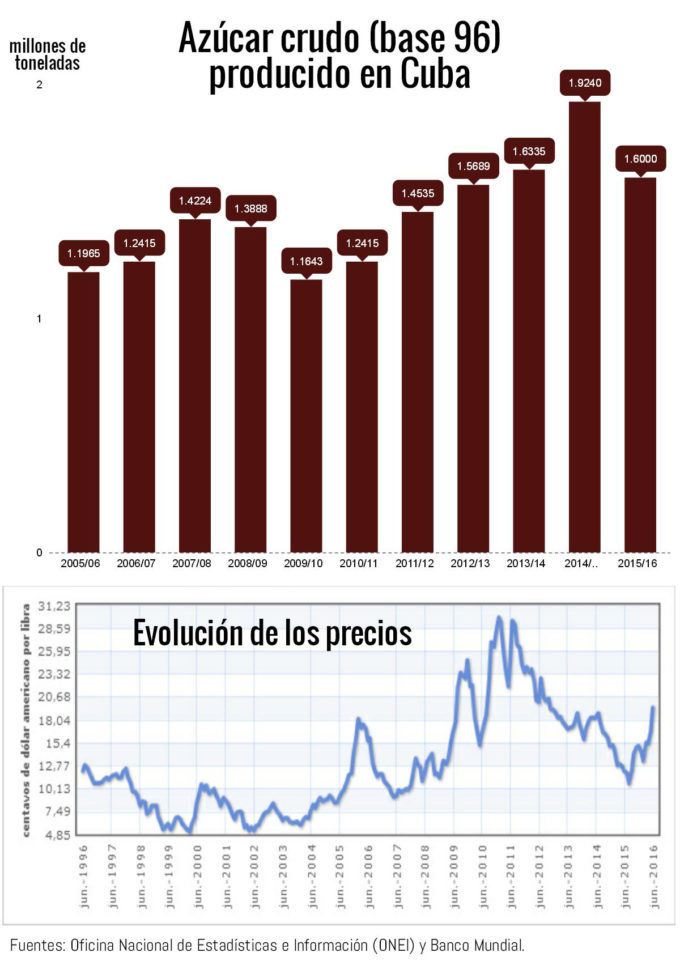

Later, prices began to recover; in 2009, they rose 90 percent in only four months. That year, Cuba’s sugar industry struck bottom when it recorded its worst harvest in a century: 1.1 million tons. In fact, since 2005, Cuba has not broken the 2 million-ton barrier.

A rebound in market prices made sugar a contributor of revenue for the country, in addition to satisfying the domestic consumption — about 700,000 tons a year. Consequently, beginning in 2011, the government encouraged both the cultivation of cane and the production of sugar.

The price of a ton of cane was set by the industry at 104 pesos (4.25 dollars) for the purpose of encouraging the cooperatives and the new private farmers to cultivate it. At the same time, the industry renegotiated the growers’ debts.

The industry also applied results-based systems of payment that raised the wages of workers and continued to invest in the modernization of transport and production technologies, in the knowledge that 93 percent of the sugar harvest is now mechanized.

The sector opened cautiously to foreign investment. In 2012, the Odebrecht Group signed a joint-venture contract to manage the 5 September Mill in Cienfuegos for 13 years. AZCUBA contracted with British-based Havana Energy for the construction of a power-generating plant fueled by biomass, near the Ciro Redondo Mill in Ciego de Ávila.

Analysts such as Armando Nova González are convinced that Cuba’s sugar agro-industry has been recovering since the massive restructuring of 2002. According to him, the industry’s potential exceeds the traditional production of sugar, whose prices are favorable in the world market.

The sugar agro-industry, Nova says, has the potential to furnish Cuba with gross revenues in excess of 4.1 billion dollars and provide about 38 percent of the current consumption of energy.

According to professor Nova, some of the main challenges facing this sector are the lack of economic incentives for farm producers, the relatively high costs of production, the low productivity of workers, and the mismatch between the domestic and international prices paid to sugar cane producers.

We need to continue practicing

Modern baseball takes much advantage of sabermetrics, a science that prioritizes the efficacy of each play over the traditional statistics. The AZCUBA Sugar Group will use a similar tool during the next sugar harvest.

On the part of the farmers, “efficiency will be the essential indicator for the assessment of the raw material needed for processing,” said Noel Casañas, the group’s vice president. “Mere fulfillment will no longer be key.”

The mills will set rules of stricter control over the quality of repairs, he added, and all mills should be in operation no later than January, in order to avoid the spring showers of May.

That strategy confirms that when it comes to sugar, as in baseball, synchronization is more important than climate.