Recruiting excellent teachers requires more than mere idealism

By Mary Sanchez

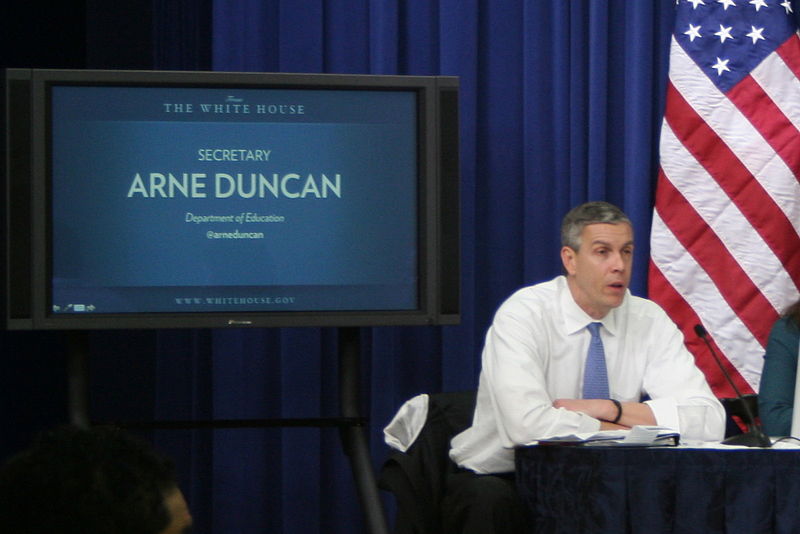

Arne Duncan wants you!

Picture that slogan on a poster. The secretary of education pointing outward like Uncle Sam, summoning the nation’s top-achieving college students to enter America’s classrooms as teachers.

Not very convincing, eh?

OK, the Department of Education’s new public service campaign, called Teach, is far more polished, but essentially it has all the honesty and appeal of “Join the Army and see the world.”

When will they learn?

Like such efforts in the past, Teach dances around some highly pertinent issues: salary, working conditions and the beatings the teaching profession takes in the political arena.

If we want to draw the brightest of our college applicants into the teaching profession, we have to be honest with ourselves about what it will take. Let’s start with money.

Compared to other high-achieving countries, U.S. teachers are not underpaid. But they are when compared to comparably trained American college graduates who enter other occupations; their salaries are 40 percent lower, according to research released last year.

Given the cost (and debt incurred) of a college education these days, a 40 percent difference is significant. American young people aren’t that bad at math. They can compute the impact on their future lifestyles.

Last year the federal government sought to infuse some respect for teachers with a $5 billion initiative dubbed RESPECT (Recognizing Educational Success, Professional Excellence and Collaborative Teaching). Duncan said its goal was to make teaching “not only America’s most important profession but also America’s most respected profession.” School districts and states competed for the funding to boost the teaching profession’s profile.

Sorry to point out the obvious, but in America, respected jobs are offered the higher salaries.

Duncan understands that the countries that perform best in standardized testing draw their teaching staffs from the best and brightest students entering colleges and universities. And he would no doubt like to make that the case in the U.S. But it’s almost as if we dare not utter the word salary or acknowledge the role it plays in influencing the choice of a profession.

“Make More. Teach” is one of the catchiest slogans of the Teach campaign. But the “more” doesn’t refer to money. Instead, in a series of advertisements, a voiceover explains: “I make learning a privilege, not a chore, and frustration a tool, not an obstacle. I make working hard seem easy and giving up impossible.”

Clever, but if we really want to draw the top talent to teaching, we have to offer them something more than this warm, fuzzy Obama-style idealism.

Improving the ranks of teachers for tomorrow requires facing head-on the attitude that education is mostly a benevolent calling, best left to those who simply “love children.” The platitude is an embarrassingly simplistic understanding of the skills it takes to be an effective teacher.

Moreover, we need to recognize that school is a place where the social problems of our nation get played out daily. Income and wealth maldistribution in America is a pathology that is glaringly apparent in our primary and secondary schools. We speak of an education crisis, but there is no crisis in school districts where the wealthy live. The rich and the comfortable middle class will always fund their public schools, and their children will be provided an excellent education.

That’s not the case for most large cities and many poor rural areas. There, teachers will struggle with scant resources, often contributing their own time and money to meet classroom needs, and face dispiriting and, frankly, insuperable problems caused by poverty and family dysfunction.

However spirited and energetic, teachers in these schools will fail. They will fail to solve problems for which “good teachers” are supposed to be some magic silver bullet. And they will be vilified for it.

For whatever reason, public school teachers have become a political punching bag. Perhaps it’s because they are one of the last bulwarks of organized labor. Perhaps it’s because they provide a convenient scapegoat for the social and economic inequality Americans don’t want to address. Maybe it’s envy, because, if they’re lucky and state and local governments hold up their end of the bargain, teachers will retire with something few private sector employees have: a defined-benefit pension.

Duncan argues America’s classrooms will soon face a labor turnover. Estimates are that more than a million teachers will retire in the four to six years. Does that pose an impending crisis or a unique opportunity?

That depends on the quality of students who choose to become teachers. But it also depends on the wisdom of policy at not just the Department of Education but at all levels of government. Public education is, but should not be, a proxy battleground for other political issues.

That’s a shame, because there is good research pointing to ways we could improve education. What we lack is the political will to do so.

Mary Sanchez is an opinion-page columnist for The Kansas City Star. Readers may write to her at: Kansas City Star, 1729 Grand Blvd., Kansas City, Mo. 64108-1413, or via e-mail at msanchez@kcstar.com.

(c) 2013, THE KANSAS CITY STAR. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC