Florida struggles to pay the tab for rejecting Obamacare

The challenge they face is figuring out how to provide healthcare for the poor without participating in a law most of the state’s GOP leadership detests. For the last 10 years, Florida (along with many other states) has relied on a fund known as the Low Income Pool, or LIP, that reimburses hospitals and health centers for the uncompensated care they provide to uninsured residents who can’t afford to pay. But that solution no longer works. Because the Affordable Care Act was designed to reduce uncompensated care by expanding insurance coverage and Medicaid, the Obama administration announced it was phasing out the LIP program. Along with other GOP-led states that refused the Medicaid expansion after the Supreme Court made it optional, Florida received a waiver to continue LIP. The Obama administration told the state that the exemption would end this year. Facing a fiscal deadline of June 30, lawmakers are planning to return to Tallahassee for a special session next month, with the goal of finding an alternative solution.

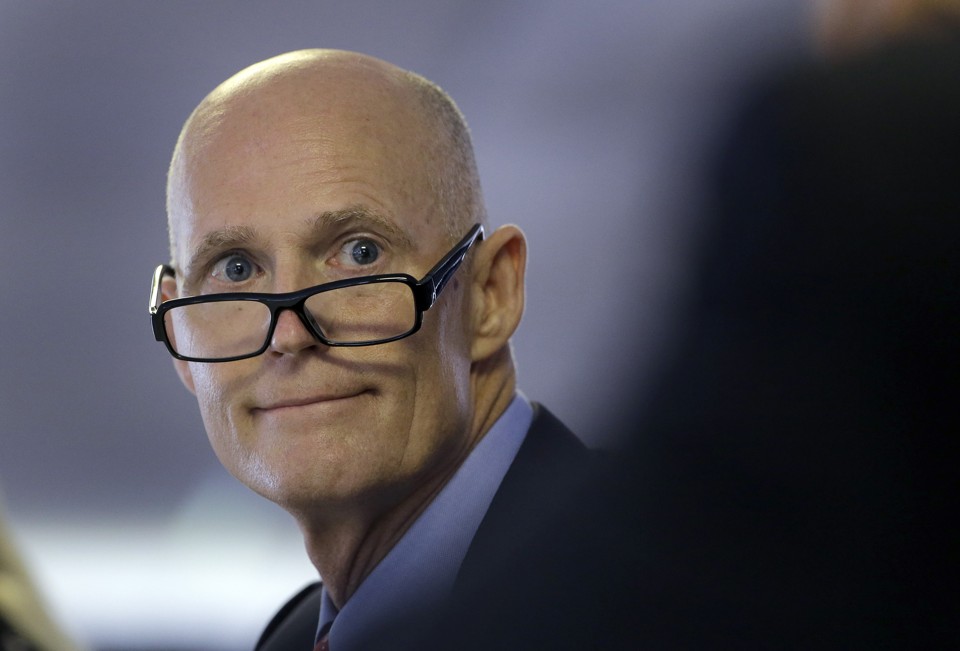

At the center of it all is Scott, the Republican who won a second term last November but whose position on the Medicaid expansion has vacillated over the years. The self-funding former healthcare executive first won the governorship on a wave of anti-Obamacare sentiment in 2010, and he opposed both the Medicaid expansion and the creation of a state insurance exchange upon taking office. But after Obama won reelection in 2012, and after the Supreme Court upheld most of the law earlier that year, Scott announced his support for expanding Medicaid at the beginning of 2013. “While the federal government is committed to paying 100 percent of the cost of new people in Medicaid, I cannot, in good conscience, deny the uninsured access to care,” he said in explaining his change-of-heart.

Last month, however, Scott flipped again. The state Senate passed a budget that including money for Medicaid expansion, but the more conservative House again resisted the change. The governor announced he could no longer trust the federal government to keep its end of the commitment, citing the state’s ongoing battle with the Obama administration over up to $2.2 billion in LIP money. Political analysts in Florida were less surprised with Scott’s announcement in April than they were when he came out in support of Medicaid two years ago. “He did nothing,” said Carol Weissert, a political scientist at Florida State University who specializes in health policy. “He was on record as supporting it after he was against it, but there was no evidence he did anything to get it done. So his support was lukewarm at best.”

Whether a more aggressive lobbying campaign by Scott could have swayed the conservative Florida House is another question. While both chambers are run by Republicans, the Senate has always been more moderate, Weissert said. And it is now led by Andy Gardiner, who, when he is not legislating, serves as an executive of a major hospital network in Orlando. A broad coalition of liberal organizations, healthcare advocates and providers, and GOP-aligned business groups rallied around the Senate Medicaid bill. In a phone interview on Thursday, Gardiner characterized the Senate’s approach as a realist position: Expanding insurance is simply more efficient and effective than reimbursing hospitals that must, by law, treat people who can’t pay. “There seems to be some acknowledgment that we have an uninsured problem in Florida,” he said. “The question is, how do you address that? Do you use state dollars, or do you use the existing program that the federal government has put out there?”

It’s the same basic argument that some other Republican state leaders have made in response to Obamacare, including Governor John Kasich in Ohio. But it had no success with the House in Florida, which for years has been an immovable force against expanding Medicaid. Nobody in the state thinks that is going to change in the next two months. “The one thing that will not be compromised in the House is we will not do Medicaid expansion,” Richard Corcoran, the Republican chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, told me. “That’s the only line in the sand that we’ve drawn.”

As Corcoran sees it, the Medicaid fight pits conservatives who oppose “a failed healthcare delivery system” on principle against an array of special interests in favor of the program. “What it really comes down to is the hospital-industrial complex wants more money, and they’ll take it even though the arguments they give are completely false,” Corcoran said. He pointed to studies showing that emergency room visits had increased since Obamacare took effect, even though Democrats trumpeted the law as a way to get people to depend on doctors for treatment, not the ER. (Research has also shown, Vox‘s Sarah Kliff notes, that people are more likely to seek care overall—including at the emergency room—when they have insurance.)

Corcoran also said the Medicaid expansion targeted a population of people who didn’t warrant government assistance. The extremely poor and the disabled are already covered under the program, while many people who are working are either insured through their employers or are eligible for subsidies to buy insurance through the Obamacare exchange that the federal government has established in Florida. “The expansion group—as described, they’re not even working. They’re not working,” Corcoran said. “The overwhelming majority is not working. When the voters—I don’t care if you’re a Democrat, Republican or independent, they don’t think they should get anything.” Weissert said many of the 870,000 to 1 million people who would be covered under a Medicaid expansion do work in Florida’s large service industry—which includes the dominate tourism sector—and may not get insurance through their jobs and don’t earn enough to qualify for a subsidy.

(From: The Atlantic)