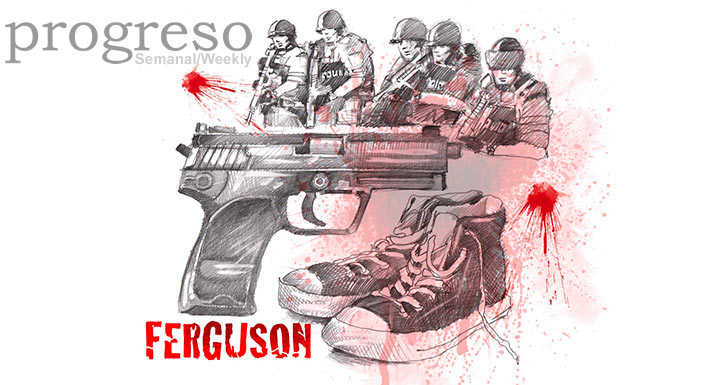

Ferguson and the reign of terror

Ferguson is no ordinary place. It is in Missouri, a state near the center of the United States, in the so-called Midwest. However, since its incorporation into the Union, it was part of the Southern slave bloc and its name is inextricably associated with the desire to perpetuate and extend slavery in the new republic.

The media point out that it is a suburb of the large city of St. Louis and that its population, mostly black, is governed by whites. Ninety percent of the police force is white.

On Aug. 9, Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager was murdered by three pistol shots, two of them to the head. The police officer who fired the shots has not been punished and was proclaimed a hero by the Ku Klux Klan, which is raising funds for his defense.

The crime has generated continuous protests that have brought together blacks and whites and an elderly Jewish woman, a Holocaust survivor who was arrested for condemning the neofascist brutality. Elsewhere in the country, solidarity grows.

The small city is an actual battlefield. There is a curfew. Through its streets, armored vehicles roll, bristling with guns, deployed by a militarized police that has been joined by National Guard troops. The latter has already killed another young man in St. Louis.

This is something that happens all too frequently and has much to do with the increase of domestic repression beginning with W. Bush and the Patriot Act. Ever since, the Pentagon and the Department of Homeland Security have supplied municipal police forces with tanks, artillery, mortars and tear gas. They keep the police SWAT teams supplied.

The victims are not always black. In October 2005, two young men, equally unarmed, were gunned down in an action that has gone unpunished; coincidentally, one of them was also named Michael Brown.

The latest event underlines the deep roots of racism in that society.

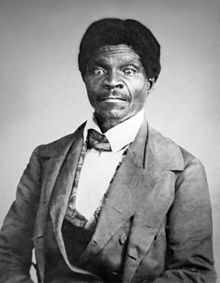

In Ferguson, very near the place where the indignant demonstrations are now taking place, on West Florissant Avenue, you’ll find the Calvary Cemetery, which holds, in a humble grave, the remains of Dred Scott.

In Ferguson, very near the place where the indignant demonstrations are now taking place, on West Florissant Avenue, you’ll find the Calvary Cemetery, which holds, in a humble grave, the remains of Dred Scott.

Few may remember him, but Scott was the protagonist of a struggle that shouldn’t be forgotten. He waged it peacefully, without violence, compelled only by his love of freedom. Scott believed passionately in his right to be a free man.

Coming from another state, where no slavery existed, he worked hard to buy his emancipation and, faced with his master’s refusal (a rich landowner from Missouri), he turned to the courts. For 11 years he pressed his case, up and down the judicial system.

Finally, in 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court, upon rejecting his petition, issued one of the most shameful rulings in its history. Among other things, the Court said that blacks were “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they [had] no rights which the white man [was] bound to respect.”

The decision coincided with the newly promulgated Fugitive Slaves Act that established the obligation to capture and return escaped servants, to whom the law denied the chance to resort to the courts. It is calculated that more than 20,000 slaves fled to Canada. One of them described those days as “the beginning of a reign of terror for colored people.”

Later came the abolition of the opprobrious system and the Civil War and one more century of struggle, until the 1964 Civil Rights Act acknowledged, on paper, the equality of blacks and whites.

However, everything indicates that the racist infamy and its reign of terror still rule in the heart of North America.