Cuba-U.S.: A healthy relationship

HAVANA — Cooperation in matters of health and medical research can be one of the most solid roads to rapprochement between two countries that are still very distant. For more than 20 years, a U.S. organization seeks to generate synergies in a sphere where both nations show remarkable results.

It is called Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC). Located in Oakland, Calif., it brings together dozens of health professionals from all over the country.

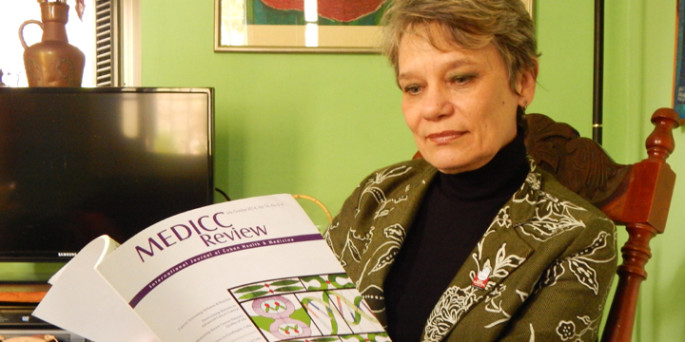

“We can’t close our eyes to the differences that exist, but our organization has the privilege of being in one of the fields where the benefits of cooperation exceed the hostility,” says Gail Reed, a Chicago journalist who, from her office in the Havana neighborhood of Santos Suárez, writes for MEDICC Review, a quarterly that translates into English the articles and research papers by doctors from Cuba and other countries.

“The association used to help us organize the trips to Cuba of students of medicine. I accompanied them from time to time,” recalls Javier Nieto, a professor at the University of Wisconsin/Madison and a member of MEDICC.

“This exchange was interrupted in 2003 or 2004 by the restrictions imposed by the Bush administration.” Until then, some 1,500 Americans were able to know first-hand the system of medical care on the island.

“The possibilities for collaboration are unlimited, beginning with academic exchanges. Cuba can contribute much to the public health organizations in the U.S. about preventive medicine, especially in disadvantaged populations,” says Nieto, adding that he’d like to visit Cuba again.

“I still have friends and colleagues there,” he explains.

One man who has been able to return to Cuba is the association’s president, Dr. William Keck, professor emeritus at Northeast Ohio Medical University.

“I’ve traveled there almost 30 times in the past 23 years. I was impressed by the efficiency and efficacy of the model of universal access to health care that they have developed. Surely we can learn from a country with scant resources that nevertheless achieves a level of health care that is equal to — or better than — ours, spending a lot less per person,” Keck argues.

“Collaboration between the two countries is not just a good idea, it’s indispensable!” emphasizes Gail Reed, who gives an example of what, in her opinion, has been the most substantial benefit for the U.S. of the exchanges promoted by MEDICC.

“Under our Community Alliance for Equity in Health, local leaders from Los Angeles, Oakland, Albuquerque and the Bronx determined their health problems and traveled to Cuba to exchange ideas with colleagues who were treating the same disorders, such as obesity, diabetes and teen pregnancy.

“Those exchanges brought forth ideas. For example, representatives from Oakland saw a family doctor in every neighborhood and wondered, ‘Why can’t we have doctors at our Fire Departments or in churches? We don’t have to build anything, just revise the local budget and bring the services closer to the people.’ And that’s what has been done,” Reed says.

Support good ideas

Ever since the creation in Havana of the Latin-American School of Medicine, MEDICC has provided support for the training of the students. It does so because it is interested in accompanying the young Americans who receive scholarships to study there.

As of 2015, some 250 young Americans with limited resources have matriculated for free in that institution, making a commitment to care for the disadvantaged communities in their homeland. The number of graduates is on the rise.

“Our help consists of finding them mentors who will keep them ‘connected’ with the U.S. health-care system during their studies,” Reed explains. “We also finance, partially or totally, the boards [exams] that determine access to medical residency in the United States. Those tests cost about $2,000 and more than 90 percent of the students come from low-income families and racial and ethnic minorities that can’t afford that much,” Reed says.

The good will demonstrated by the NGO has earned it much prestige among Cuban professionals. Pedro Urra, the founder and longtime director of INFOMED, the Health Ministry’s computer network, defines it as “a serious and responsible channel […] because it has visualized the reality of Cuban public health and has brought experts from both countries together in a climate of respect and dialogue.”

That value is what the organization wants to use to promote binational agreements.

“We’re expecting the visit to Havana in April of two groups of members of the American Association of Public Health, whom we helped to sign a memorandum of understanding with the Cuban Public Health Society,” Reed says.

The experience gained from dealing with the regulations and political stances of both countries is another tool in the hands of MEDICC, useful to advise potential U.S. investors in the pharmaceutical industry or medical research.

“Total cooperation will not be possible until the embargo is revoked,” argues president Keck.

“The reduction in restrictions can facilitate initial efforts of joint research, but it’s not clear what will happen when dollars from the U.S. are involved. Besides, past experience will make Cubans very cautious when dealing with Americans. Add to this the fact that the health sector in Cuba has been directed by the State for a long time and the profits remain under central control to provide services, supplies, medications and equipment.

“The marked differences with the U.S. perspective of managing can stress the partners,” he says.

“Advances in Cuban biotechnology should be subjected to the same tests of the Federal Drug Administration as the rest of the world’s products,” the journalist insists. “American patients and doctors have the right, for example, to use Heberprot-P, a product that could prevent many of the 70,000 or 80,000 amputations for diabetic foot that are reported every year in the U.S.”

“It is important that Americans get to know the culture, history and advances that have been made in Cuba as a result of a major investment in human resources. I would like Americans to be sensitive to the problems of a poor country like Cuba, and I hope that the U.S. won’t continue to contribute to those problems.”

That could be the basis for a — well — healthy relationship.

Photo at top: Gail Reed, correspondent of MEDICC in Havana.