Bachelet: No amnesty for Pinochet’s minions

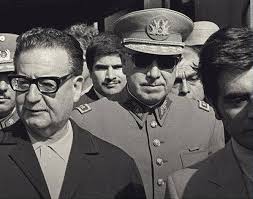

On the 41st anniversary of the military coup d’état that took the life of Chilean President Salvador Allende Gossens, President Michelle Bachelet announced that her administration will seek to revoke — “with urgency” — an amnesty law that shields military personnel from trial for the crimes they committed between 1973 and 1978.

President Bachelet made the announcement in Santiago during a ceremony at La Moneda Palace that honored Allende, who assumed power in November 1970 and took his own life on Sept. 11, 1973, when Army Gen. Augusto Pinochet ordered a full-blown attack on the presidential palace.

In the years following the coup, civil and human rights were repeatedly violated by the military regime imposed by Pinochet, which lasted until 1990.

Repeal of the amnesty law, enacted in 1978, was one of President Bachelet’s campaign promises.

“Today, again in democracy, Chile has not lost its memory. Chile has not forgotten its persecuted, executed, arrested and disappeared children,” Bachelet said Thursday. “Chile has not forgotten those who kept alive the hope of a free country.”

“Enough of painful expectations and unjustified silence,” she told the audience in the palace courtyard. “The time has come to truly become brothers. And to do this, it is essential that those who have relevant information, be they civilians or military, turn it in.”

Before the official ceremony, Bachelet walked into Allende’s former office and placed a white rose on the sofa where his body was found after the coup.

Senator Isabel Allende, the late President’s daughter, who is now president of the Senate, praised Bachelet’s avowed task.

“Even today, we have not been able to determine the fate of many of those who were arrested and disappeared and we need to know the truth,” she said. At one point during the ceremony, Ms. Allende broke into tears and was consoled by President Bachelet.

Repeal of the law requires a simple majority in Congress. In practice, Chilean courts do not apply it and try former military personnel who are proven to have participated in criminal activities during the Pinochet regime. In that sense, a move to repeal would be only symbolic.

At least 250 individuals have been tried and sentenced for crimes during the coup’s aftermath. Human rights organizations argue that the very existence of the law is incompatible with Chile’s obligations as a democracy.

Passage of a motion to repeal should not be difficult: the ruling center-left coalition has a majority in both houses of Parliament.

Between 1973 and 1990, about 3,000 Chileans died or disappeared and 28,000 were imprisoned and tortured, including Michelle Bachelet Jeria.