An American in Cuba

HAVANA — They say that journalists make the worst interviewees. If that were true — and there is no proof that it is — Conner Gorry would be an exception. “Yo soy muelera” [“I am a jabberer”], she says in her slang-peppered Spanish.

She’s a New Yorker by birth, writer by choice and a traveler on an indefinite stopover in Havana. She first landed here in 1993, when she came to do voluntary labor in the fields while finishing her master’s degree on the U.S. blockade against the island.

“The Cubans have a way of facing life that inspired me,” she says. “Cuba is more in line with my personal principles: to think about the most vulnerable, about all of society. In the United States, there is this culture of ‘me, me, me,’ and that’s not my philosophy, has never been.”

Nine years later, she fell in love with a Cuban, got married and stayed. But happiness is also a process. The two Bush presidential terms were very difficult for her, barely able to communicate with her family in New York, which couldn’t come to Cuba.

“Conner,” her mother chided her, “why didn’t you fall in love with a Miami Cuban?”

“I looked at her as if saying, ‘you know why.'”

The gringa next door

That’s how Conner introduces herself in her blog Here is Havana, a “campaign diary” where she tells how she lives — joy, self-employed work, resistance, absurdities. She likes to compose lists: Six Damned Cuban Customs; A Cuban Glossary; Just When You Think You Know Cubans.

“I launched a blog because some Cuban bloggers made me very angry. They were projecting a vision of Cuba that made me think, ‘But where do those people live?

“If you truly want to give a vision of how this country is, you have to look at the good, the bad and the average — an analysis that shows the variety of circumstances.”

As an explorer or an ancient messenger, Conner moves forward, studies the terrain and then narrates her experiences to others. “Things are complicated here,” she says, as someone who after 14 years still cannot understand some things. Who can do that, anyway?

“I recommend that you take this into account: respect, listen. There are tourists who spend five days here and have an answer for all the problems. And I say to them, ‘Oh, how interesting that in five days you came to these conclusions. The Cubans have been working at it for 20 years and they still don’t have the answers, but you do.’

“Before I came here, I knew that people put their expectations about Cuba, their prejudices, through a very personal lens. But one doesn’t know how a place is until one touches it with one’s own feet, one’s own hands. Much of my work has been writing to break those myths, to share information about the Cuban reality.”

President Obama

“For me, his visit is the aperitif. ‘The chicken in the chicken-with-rice’ this week is the Rolling Stones. I am very cynical about the United States. Obama has guts, that’s a fact, and I congratulate him.

“This has been the first time that I’ve heard a U.S. president say that the Cubans have the right to make their own policy. But the United States still has a colonial mindset. They want reforms, they want to influence the system that exists here. And that’s like, ‘Hey, mind your own household, not mine.'”

Café – Bookstore – Oasis

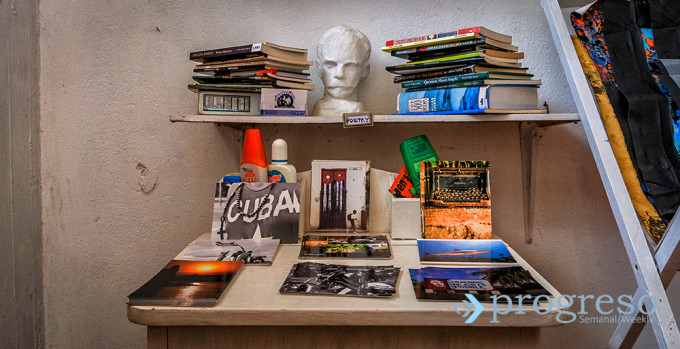

Cuba Libro has three purposes; it’s a place that welcomes faithful regulars, foreign students and the (many) friends of the house. Conner created it two years ago and defines it as “an ethically and socially responsible business, because the private sector has obligations to the community where it functions.”

“Reading is sexy,” says a sign inside. The shelves hold English-language literature. Next to the door, you find more or less recent issues of Fortune, The New Yorker, The Nation and The Economist.

Saint Lazarus, the saint of Cuba-U.S. normalization, protects some of the books on the higher shelves.

On Dec. 17, 2014, Conner was here. “The Obama announcement was on the TV set in the dining room and Raúl’s speech was on the TV in the living room, and we kept running between the two sets. It was so unexpected. I couldn’t believe that there had been no ‘runruns’ [rumors.]

“A lot of people were involved in the negotiations and the Cubans are not very good at keeping secrets. Right away, I thought, ‘How many people kept that secret?'”

Afterward, they bought a bottle of rum and toasted. “I never thought that I would live to see that moment.”

‘See Cuba before it loses its old charm’

“That’s a very neocolonialist perspective. Ah, you want the buildings to continue to crumble? Do you want the man who owns a vintage car not to have access to a modern car? Sure, a slum is very quaint. That annoys me a bit because it’s unfair, I believe.

“The Cubans deserve more; they deserve a just and sustainable development. The tourist who wants to see a Cuba that’s poor or antique is like [singer] Rihanna in Havana; she posed wearing $2,000 shoes in front of buildings that were collapsing from old age. Hey, no; that’s a lack of respect.”

They and me

Conner speaks in plural when she refers to the circumstances and people who surround her. When she says “we are an island,” or “we still have the inverted pyramid,” one can only sympathize with this woman who took on problems that technically were not her own.

The natives, so famous for their solidarity, not always got the message. “I got around in camellos [old buses], did guard duty in the CDR [neighborhood surveillance teams], but the ordinary Cuban saw me as ‘that woman who arrived from the North three days ago.’ I’ve been put through everything: the Cuban con game, the bait-and-switch game…”

“My friend, my friend, where are you from?” some wiseguy would ask her.

“Where am I from? From 100th Street and Boyeros,” she would answer, when she lived at that address.

“Now it’s funny, but at first it was hard for me to adjust. I was very committed but not accepted. Sometimes I thought, well, what must I do to make Cubans see me as an ally, a source of support, a friend, rather than a dollar bill or someone on holiday.

“That has improved, because, with so many tourists, people look at my ragged tennis shoes and say, ‘Ah, that one might be a tourist, but she’s not wealthy.'”

As a reporter for MEDICC Review, Conner traveled with the Henry Reeve Brigade to Pakistan and Haiti. There, the doctors called her “the Yuma-Cuban journalist.” Having her own nickname made her feel acknowledged, even happy.

Right after opening Cuba Libro, she discovered how many foreigners live on the island. Few of them are American. “There are students from U.S. universities who spend a semester here. There are anthropologists and academicians. But it’s not the same.

“They don’t have to deal with fumigating every week, filling the cooking gas tank, communicating with the family abroad, standing in line at the grocery store. For them, it’s like a war dispatch: ‘Oooh, a daylong power outage.’

“When you live here and become a local, you have to learn to do things Cuban-style.”