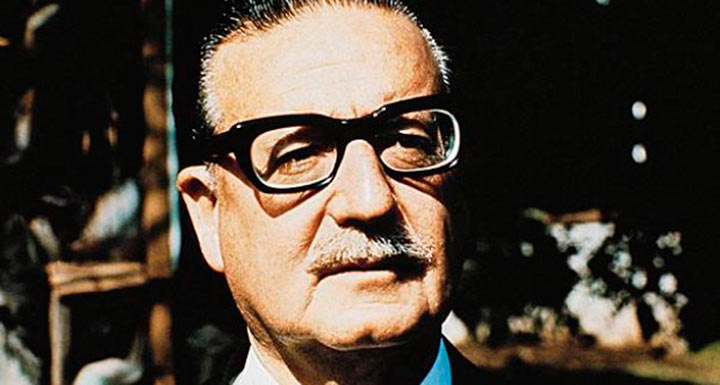

‘Allende, the death of a president’

NEW YORK — One week away from Sept. 11, a very tough day in this city, the barely bearable weight of the 3,000 victims of the World Trade Center Tragedy again presses on the five counties.

It has been this way since 2001. When this sorrowful day nears, the elapsed years disappear and people are gripped by a slow and strange quietude that is normally unknown in this bustling city.

But Sept. 11 is a tragic date not only in the United States. On that day, Chile also darkens at the memory of the death of President Salvador Allende and the coup d’état staged by Gen. Augusto Pinochet in 1973 with Washington’s support.

On that day, Chileans remember with pain the way the chief of his country’s armed forces betrayed the democratically elected president of Popular Unity and his people, to whom Pinochet subjected to 17 years of terror, disappearances, torture and murder.

About this, and about his stage monologue “Allende, the death of a president,” we spoke with Argentine writer and journalist Rodolfo Quebleen, who has lived in New York since 1965.

“Allende” has been shown more than 250 times since its English-language premiere in 2006 at the Theater for the New City, where it ran for two seasons.

Since then, it has toured Venezuela, Chile and Argentina, where it was shown until last Saturday (Aug. 30). Such has been the monologue’s impact that the Argentine Ministry of Culture has declared it a “work of cultural interest.” Its author says he would like to see it shown in theaters in Cuba and Spain.

An anecdote that conveys the timeliness of “Allende” occurred in 2008, when the show opened in Caracas.

“President Chávez went to the premiere and, after the show ended, walked up to the stage and said that something like that might occur in Venezuela but that he wouldn’t allow it,” Quebleen recalls. “‘I’m going to defend democracy by blood and fire,’ Chávez said, very moved, identifying himself with the Chilean president.”

The one-man show, which takes place during Allende’s final hour at the presidential palace La Moneda during the coup, “is a race against time to review his management of government, analyze the current situation and delve into personal remembrances,” says Quebleen, who relied on recordings, the testimony of survivors and even CIA files.

On the stage we see a desk with some books and two telephones, and a flagpole with the Chilean flag. We see a president who is alone and disappointed but responds to the putschists with the cry: “Allende doesn’t surrender, you shitty maggots!” Rifle in hand, he prepares to fight to the last.

“The rifle was a gift from Fidel Castro and bore a dedication that said ‘To Salvador Allende, from his comrade-in-arms, Fidel Castro,” says Quebleen. “At the supreme moment in his life, the Chilean president defended himself or committed suicide with Fidel’s rifle.”

Why the monologue? The answer is given by its author, who met Allende personally in 1972, when he interviewed him at the United Nations for the newspaper ABC of the Americas.

“When he was murdered, I was horrified. I had to do something, I thought. I tried a novel and a stage play but neither project jelled. But I still felt that I should do something to make [Allende] walk again, to help him come to life, so I finally wrote the monologue about his final hour, the most important in his life because he then confirmed what he had always said. He didn’t take a step back; he didn’t surrender. He died as he promised, defending the constitutionality and preserving the dignity of the presidency.”

Almost half a century has passed since the death of Allende, the first statesman to attempt a socialist revolution by democratic means in Latin America. If he lived today, he would be pleased by the half-dozen countries that are “trying to do something else,” Quebleen opines.

“In his country, the situation is moving close to his agenda. President Bachelet’s agenda is similar to his but is handled very cautiously. No one should forget that, unlike Argentina and Uruguay, Chile still has an army and a military police presence. No doubt, Allende today would have a connection with the current situation, with Evo, Correa and Chávez, of course.”

Things have changed much in Latin America in the 41 years since Allende’s death. “Today, he would have reason to feel plenty satisfied,” Quebleen says.

That’s the best tribute that could be paid to him on Sept. 11, 2014.